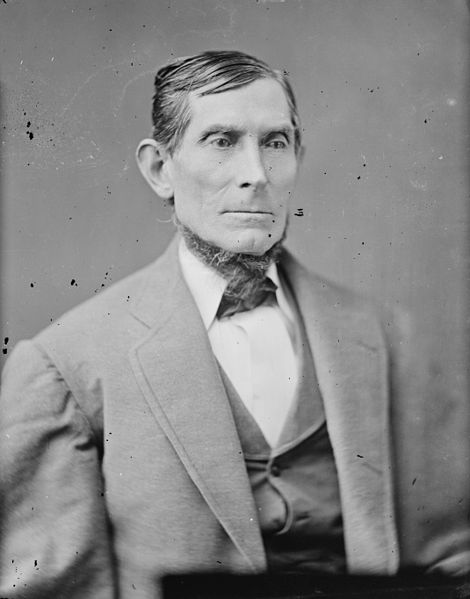

James Douglas Williams (January 16, 1808 - November 20, 1880), nicknamed Blue Jeans Bill, was a farmer and Democratic politician who held public office in Indiana for four decades, and was the only farmer elected as the Governor of Indiana, serving from 1877 to 1880. He also spent twenty-eight years in the Indiana General Assembly, and was well known for his frugality and advocacy of agricultural development.

Early life

Family and background

James Douglas Williams was born on January 16, 1808 in Pickaway County, Ohio, the son of George and Sarah Cavendar Williams. He moved with his family to Knox County, Indiana at the age of 10, and his family moved and settled near Monroe City, Indiana where he remained much of the rest of his life. He received little schooling, but did occasionally attend the log schoolhouse near his home, only attending until the fifth grade. Williams' father died in 1828, and being the oldest son, Williams became the caretaker of his family, continuing to run his father's farm. In 1831 Williams married Nancy Huffman, and together they had seven children. With Williams regularly in public service, she ran the family farm for much of her life—a three thousand acre spread in the central part of Indiana.

Throughout his life, Williams was known for his farm dress, earning him the nickname Blue Jeans Bill, because he so often wore denim. He used the nickname and the reputation that came with it to cast himself as a man of the people, and a countryman in his public elections. As he became more wealthy, he began to have suits made of denim and lined with silk. Besides being a farmer, Williams was active in studies and experimentation in trying to produce superior crops. He was a member of several local and regional farm organizations and regularly won first place in many of the Indiana State Fair competitions.

Legislator

In 1839 Williams first entered public service serving as justice of the peace of Vincennes, Indiana until he resigned in 1843. The same year he was elected to the Indiana House of Representatives and served until 1860, moving to the Indiana Senate where he served until 1872. Williams was responsible for the authorship of many bills, including laws that permitted widows to inherit the estate of their husbands. He wrote the bill that established the state's first sinking fund and also encouraged the development of the State Board of Agriculture and served as a member for sixteen years.

During the American Civil War, Williams was accused of being a Copperhead when he attempted to interfere with the war effort and submitted legislation to require Governor Oliver Morton to show what the money in the state emergency fund was being spent on. One of Williams's primary concerns in the Assembly was state spending. He supported the Greenback political movement that began in the 1870s, making paper money more readily available to the public through inflationary measures. His long term membership in the party led them to attempt to send him to Congress as a Senator in 1872, but was defeated by Oliver Morton. Williams was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Indiana in October, 1874 and served from 1875 to 1876. During this time he served as chairman of the committee on accounts and was responsible for considerable reform, and significant saving by cutting business costs. "A more destructive besom of economy could not have been selected from all the ranks of the democracy, or from either party, for that matter,"one observer wrote. "Lank, for all the world like Lincoln, and as tall, with a face which might be photographed for Lincoln's, and a shambling gait and a carelessness of dress exactly like the dead president's, Williams is a figure that never fades from the minds of the thousands who have once seen him," a reporter wrote. "Dressed always in the plainest of plain Kentucky blue jeans, he is a standing reproach to the more luxurious livers of his own party." While still in Washington he was informed that his party had nominated him to run for governor, a nomination he was not a candidate for. Instead of declining, he decided to not seek re-election to Congress, but instead returned to Indiana to campaign for governor.

Governor

Williams owed his nomination for governor to a deadlocked Democratic convention and he ran against future Republican President Benjamin Harrison and Greenback candidate Anson Wolcott. The campaign focused predominantly on federal financial positions that had caused a financial downturn. Williams changed his position on the Greenback movement, and came out against the inflationary practices. But the campaign was also centered around personality, and there Williams had a tremendous advantage. "Blue Jeans Williams would never think that it was necessary to set about his day's work with his hair parted in the middle and his beard trimmed like a row of tree box," a reporter gibed; "the other emerges from his toilet with the appearance of one who used considerably the hairbrush and the oil bottle. Harrison dresses in Broadway fashion; Williams in 'blue jeans.' Harrison is a smart lawyer, to whom Governor Hendricks gave the best part of his practice. Williams is an honest old farmer, who has earned every cent he owns by the sweat of his brow. Harrison is a cold, reserved, chicken-broth order of man. Williams is an open, warm-hearted, horny-handed farmer, with broad acres to which he can point as the result of long years of patient struggling with nature." Williams won in a close election by about 5,000 votes. Williams became the only person whose primary source of income came from farming to be elected Governor of Indiana. He was inaugurated on January 9, 1877.

He was instrumental in finding the funds for Purdue University and was a women's rights activist, championing the right for women to own property. He fought for budgetary constraint and was known for his thrift, most evident in the construction of the new Indiana Statehouse. During his administration he sought and acquired funds for the construction of a new state capitol building. He was able to have the building built for about 20% less than was initially expected, and returned the saving to the treasury. Although he wanted to run the government with economy, he sought increased funding for the state assistance programs for war veterans.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 began during Williams' term. Strikers in Indianapolis attempted to block all rail traffic in the city. City and business leaders demanded that Williams call out the militia and end the strike by force, but he refused fearing it would hurt his standing in the Democratic party. Since Williams refused to engage the workers, Benjamin Harrison and Walter Q. Gresham, the state's leading Republicans, formed a commission to meet with business leaders and end the strike. The situation caused considerable harm to Williams public popularity. Many parts of the nation were experiencing a rapid industrial growth during Williams term, and he did little to emulate their success in Indiana, leading to some criticism.

Death and legacy

Williams' wife suffered a fall in January, 1880 and died on June 27, 1880. Starting in late October 1880, Williams developed a kidney infection. His health steadily deteriorated and he died shortly before the end of his term as governor in Indianapolis, on November 20, 1880. His bier was held in the Marion County Courthouse before his body was moved Vincennes for a funeral ceremony. Williams is buried in the Walnut Grove Cemetery near Monroe City, Indiana cemetery on ground he donated to establish Walnut Grove Methodist Church near his home. His family purchased a large obelisk for his grave which was unveiled on July 4, 1883, and it still stands above the tiny Bedford Stone church to this day. Many of the members of the church are Williams descendants.

Electoral history

| Indiana gubernatorial election, 1876 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | James D. Williams | 213,219 | 49.1 | |

| Republican | Benjamin Harrison | 208,080 | 47.9 | |

| Greenback | Anson Woolcott | ?? | ||

[ Source: Wikipedia ]