Died: August 16, 1948 (at age 53)

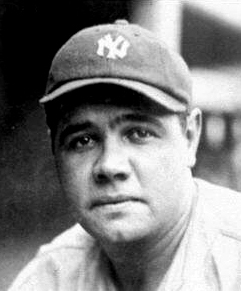

George Herman Ruth Jr. (February 6, 1895 - August 16, 1948) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed "The Bambino" and "The Sultan of Swat", he began his MLB career as a stellar left-handed pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, but achieved his greatest fame as a slugging outfielder for the New York Yankees. Ruth established many MLB batting (and some pitching) records, including career home runs (714), runs batted in (RBIs) (2,213), bases on balls (2,062), slugging percentage (.690), and on-base plus slugging (OPS) (1.164); the latter two still stand today. Ruth is regarded as one of the greatest sports heroes in American culture and is considered by many to be the greatest baseball player of all time. He was one of the first five inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936.

At age seven, Ruth was sent to St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys, a reformatory where he learned life lessons and baseball skills from Brother Matthias Boutlier of the Christian Brothers, the school's disciplinarian and a capable baseball player. In 1914, Ruth was signed to play minor-league baseball for the Baltimore Orioles but was soon sold to the Red Sox. By 1916, he had built a reputation as an outstanding pitcher who sometimes hit long home runs, a feat unusual for any player in the pre-1920 dead-ball era. Although Ruth twice won 23 games in a season as a pitcher and was a member of three World Series championship teams with Boston, he wanted to play every day and was allowed to convert to an outfielder. With regular playing time, he broke the MLB single-season home run record in 1919.

After that season, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee controversially sold Ruth to the Yankees, an act that, coupled with Boston's subsequent championship drought, popularized the "Curse of the Bambino" superstition. In his 15 years with New York, Ruth helped the Yankees win seven American League (AL) championships and four World Series championships. His big swing led to escalating home run totals that not only drew fans to the ballpark and boosted the sport's popularity but also helped usher in the live-ball era of baseball, in which it evolved from a low-scoring game of strategy to a sport where the home run was a major factor. As part of the Yankees' vaunted "Murderer's Row" lineup of 1927, Ruth hit 60 home runs, extending his MLB single-season record. He retired in 1935 after a short stint with the Boston Braves. During his career, Ruth led the AL in home runs during a season twelve times.

Ruth's legendary power and charismatic personality made him a larger-than-life figure in the "Roaring Twenties". During his career, he was the target of intense press and public attention for his baseball exploits and off-field penchants for drinking and womanizing. His often reckless lifestyle was tempered by his willingness to do good by visiting children at hospitals and orphanages. He was denied a job in baseball for most of his retirement, most likely due to poor behavior during parts of his playing career. In his final years, Ruth made many public appearances, especially in support of American efforts in World War II. In 1946, he became ill with cancer, and died two years later.

George Herman Ruth Jr. was born in 1895 at 216 Emory Street in Pigtown, a working-class section of Baltimore, Maryland, named for its meat-packing plants. Its population included recent immigrants from Ireland, Germany and Italy, and African Americans. Ruth's parents, George Herman Ruth, Sr. (1871-1918), and Katherine Schamberger, were both of German American ancestry. According to the 1880 census, his parents John and Mary were born in Maryland. The paternal grandparents of Ruth, Sr. were from Prussia and Hanover, respectively. Ruth, Sr. had a series of jobs, including lightning rod salesman and streetcar operator, before becoming a counterman in a family-owned combination grocery and saloon on Frederick Street. George Ruth Jr. was born in the house of his maternal grandfather, Pius Schamberger, a German immigrant and trade unionist. Only one of young George's seven siblings, his younger sister Mamie, survived infancy.

Many aspects of Ruth's childhood are undetermined, including the date of his parents' marriage. When young George was a toddler, the family moved to 339 South Woodyear Street, not far from the rail yards; by the time the boy was 6, his father had a saloon with an upstairs apartment at 426 West Camden Street. Details are equally scanty about why young George was sent at the age of 7 to St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys, a reformatory and orphanage. As an adult, Babe Ruth suggested that not only had he been running the streets and rarely attending school, he was drinking beer when his father was not looking. Some accounts say that, after a violent incident at his father's saloon, the city authorities decided this environment was unsuitable for a small child. At St. Mary's, which George Jr. entered on June 13, 1902, he was recorded as "incorrigible"; he spent much of the next twelve years there.

Although St. Mary's inmates received an education, students were also expected to learn work skills and help operate the school, particularly once the boys turned 12. Ruth became a shirtmaker, and was also proficient as a carpenter. He would adjust his own shirt collars, rather than having a tailor do it, even during his well-paid baseball career. The boys, aged 5 to 21, did most work around the facility, from cooking to shoemaking, and renovated St. Mary's in 1912. The food was simple, and the Xaverian Brothers who ran the school insisted on strict discipline; corporal punishment was common. Ruth's nickname there was "Niggerlips", as he had large facial features and was darker than most boys at the all-white reformatory.

Ruth was sometimes allowed to rejoin his family, or was placed at St. James's Home, a supervised residence with work in the community, but he was always returned to St. Mary's. He rarely was visited by his family; his mother died when he was 12 and by some accounts, he was permitted to leave St. Mary's only to attend the funeral. How Ruth came to play baseball there is uncertain: according to one account, his placement at St. Mary's was due in part to repeatedly breaking Baltimore's windows with long hits while playing street ball; by another, he was told to join a team on his first day at St. Mary's by the school's athletic director, Brother Herman, becoming a catcher even though left-handers rarely play that position. During his time there he also played third base and shortstop, again unusual for a left-hander, and was forced to wear mitts and gloves made for right-handers. He was encouraged in his pursuits by the school's Prefect of Discipline, Brother Matthias Boutlier, a native of Nova Scotia. A large man, Brother Matthias was greatly respected by the boys both for his strength and for his fairness. For the rest of his life, Ruth would praise Brother Matthias, and his running and hitting styles closely resembled his teacher's. Ruth stated, "I think I was born as a hitter the first day I ever saw him hit a baseball." The older man became a mentor and role model to George; biographer Robert W. Creamer commented on the closeness between the two:

Ruth revered Brother Matthias ... which is remarkable, considering that Matthias was in charge of making boys behave and that Ruth was one of the great natural misbehavers of all time. ... George Ruth caught Brother Matthias' attention early, and the calm, considerable attention the big man gave the young hellraiser from the waterfront struck a spark of response in the boy's soul ... blunted a few of the more savage teeth in the gross man whom I have heard at least a half-dozen of his baseball contemporaries describe with admiring awe and wonder as "an animal."

The school's influence remained with Ruth in other ways: a lifelong Catholic, he would sometimes attend Mass after carousing all night, and he became a well-known member of the Knights of Columbus. He would visit orphanages, schools, and hospitals throughout his life, often avoiding publicity. He was generous to St. Mary's as he became famous and rich, donating money and his presence at fundraisers, and spending $5,000 to buy Brother Matthias a Cadillac in 1926—subsequently replacing it when it was destroyed in an accident. Nevertheless, his biographer Leigh Montville suggests that many of the off-the-field excesses of Ruth's career were driven by the deprivations of his time at St. Mary's.

Most of the boys at St. Mary's played baseball, with organized leagues at different levels of proficiency. Ruth later estimated that he played 200 games a year as he steadily climbed the ladder of success. Although he played all positions at one time or another (including infield positions generally reserved for right-handers), he gained stardom as a pitcher. According to Brother Matthias, Ruth was standing to one side laughing at the bumbling pitching efforts of fellow students, and Matthias told him to go in and see if he could do better. After becoming the best pitcher at St. Mary's, in 1913, when Ruth was 18, he was allowed to leave the premises to play weekend games on teams drawn from the community. He was mentioned in several newspaper articles, for both his pitching prowess and ability to hit long home runs.

In early 1914, Ruth was signed to a professional baseball contract by Jack Dunn, owner and manager of the minor-league Baltimore Orioles, an International League team. The circumstances of Ruth's signing cannot be stated with certainty, with historical fact obscured by stories that cannot all be true. By some accounts, Dunn was urged to attend a game between an all-star team from St. Mary's and one from another Xaverian facility, Mount St. Mary's College. Some versions have Ruth running away before the eagerly awaited game, to return in time to be punished, and then pitching St. Mary's to victory as Dunn watched. Others have Washington Senators pitcher Joe Engel, a Mount St. Mary's graduate, pitching in an alumni game after watching a preliminary contest between the college's freshmen and a team from St. Mary's, including Ruth. Engel watched Ruth play, then told Dunn about him at a chance meeting in Washington. Ruth, in his autobiography, stated only that he worked out for Dunn for a half-hour, and was signed. According to biographer Kal Wagenheim, there were legal difficulties to be straightened out as Ruth was supposed to remain at the school until he turned 21.

The train journey to spring training in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in early March was likely Ruth's first outside the Baltimore area. The rookie ballplayer was the subject of various pranks by the veterans, who were probably also the source of his famous nickname. There are various accounts of how Ruth came to be called Babe, but most center on his being referred to as "Dunnie's babe" or a variant. "Babe" was at that time a common nickname in baseball, with perhaps the most famous to that point being Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher and 1909 World Series hero Babe Adams, who appeared younger than he was.

Babe Ruth's first appearance as a professional ballplayer was in an intersquad game on March 7, 1914. Ruth played shortstop, and pitched the last two innings of a 15-9 victory. In his second at bat, Ruth hit a long home run to right, which was reported locally to be longer than a legendary shot hit in Fayetteville by Jim Thorpe. His first appearance against a team in organized baseball was an exhibition against the major-league Philadelphia Phillies: Ruth pitched the middle three innings, giving up two runs in the fourth, but then settling down and pitching a scoreless fifth and sixth. The following afternoon, Ruth was put in during the sixth inning against the Phillies and did not allow a run the rest of the way. The Orioles scored seven runs in the bottom of the eighth to overcome a 6-0 deficit, making Ruth the winning pitcher.

Once the regular season began, Ruth was a star pitcher who was also dangerous at the plate. The team performed well, yet received almost no attention from the Baltimore press. A third major league, the Federal League, had begun play, and the local franchise, the Baltimore Terrapins, restored that city to the major leagues for the first time since 1902. Few fans visited Oriole Park, where Ruth and his teammates labored in relative obscurity. Ruth may have been offered a bonus and a larger salary to jump to the Terrapins; when rumors to that effect swept Baltimore, giving Ruth the most publicity he had experienced to date, a Terrapins official denied it, stating it was their policy not to sign players under contract to Dunn.

The competition from the Terrapins caused Dunn to sustain large losses. Although by late June the Orioles were in first place, having won over two-thirds of their games, the paid attendance dropped as low as 150. Dunn explored a possible move by the Orioles to Richmond, Virginia, as well as the sale of a minority interest in the club. These possibilities fell through, leaving Dunn with little choice other than to sell his best players to major league teams to raise money. He offered Ruth to the reigning World Series champions, Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics, but Mack had his own financial problems. The Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants expressed interest in Ruth, but Dunn sold his contract, along with those of pitchers Ernie Shore and Ben Egan, to the Boston Red Sox of the American League (AL) on July 4. The sale price was announced as $25,000 but other reports lower the amount to half that, or possibly $8,500 plus the cancellation of a $3,000 loan. Ruth remained with the Orioles for several days while the Red Sox completed a road trip, and reported to the team in Boston on July 11.

Ruth arrived in Boston on July 11, 1914, along with Egan and Shore. Ruth later told of meeting the woman he would first marry, Helen Woodford, that morning—she was then a 16-year-old waitress at Landers Coffee Shop, and Ruth related that she served him when he had breakfast there. Other stories, though, suggest the meeting happened on another day, and perhaps under other circumstances. Regardless of when he began to woo his first wife, he won his first game for the Red Sox that afternoon, 4-3, over the Cleveland Naps. He pitched to catcher Bill Carrigan, who was also the Red Sox manager. Shore was given a start by Carrigan the next day; he won that and his second start and thereafter was pitched regularly. Ruth lost his second start, and was thereafter little used. As a batter, in his major-league debut, Ruth went 0-for-2 against left-hander Willie Mitchell, striking out in his first at bat, before being removed for a pinch hitter in the seventh inning. Ruth was not much noticed by the fans, as Bostonians watched the Red Sox's crosstown rivals, the Braves, begin a legendary comeback that would take them from last place on the Fourth of July to the 1914 World Series championship.

Egan was traded to Cleveland after two weeks on the Boston roster. During his time as a Red Sox, he kept an eye on the inexperienced Ruth, much as Dunn had in Baltimore. When he was traded, no one took his place as supervisor. Ruth's new teammates considered him brash, and would have preferred him, as a rookie, to remain quiet and inconspicuous. When Ruth insisted on taking batting practice despite his being both a rookie who did not play regularly, and a pitcher, he arrived to find his bats sawn in half. His teammates nicknamed him "the Big Baboon", a name the swarthy Ruth, who had disliked the nickname "Niggerlips" at St. Mary's, detested. Ruth had received a raise on promotion to the major leagues, and quickly acquired tastes for fine food, liquor, and women, among other temptations.

Manager Carrigan allowed Ruth to pitch two exhibition games in mid-August. Although Ruth won both against minor-league competition, he was not restored to the pitching rotation. It is uncertain why Carrigan did not give Ruth additional opportunities to pitch. There are legends—filmed for the screen in The Babe Ruth Story (1948)—that the young pitcher had a habit of signaling his intent to throw a curveball by sticking out his tongue slightly, and that he was easy to hit until this changed. Creamer pointed out that it is common for inexperienced pitchers to display such habits, and the need to break Ruth of his would not constitute a reason to not use him at all. The biographer suggested that Carrigan was unwilling to use Ruth due to poor behavior by the rookie.

On July 30, 1914, Boston owner Joseph Lannin had purchased the minor-league Providence Grays, members of the International League. The Providence team had been owned by several people associated with the Detroit Tigers, including star hitter Ty Cobb, and as part of the transaction, a Providence pitcher was sent to the Tigers. To soothe Providence fans upset at losing a star, Lannin announced that the Red Sox would soon send a replacement to the Grays. This was intended to be Ruth, but his departure for Providence was delayed when Cincinnati Reds owner Garry Herrmann claimed him off waivers. After Lannin wrote to Herrmann explaining that the Red Sox wanted Ruth in Providence so he could develop as a player, and would not release him to a major league club, Herrmann allowed Ruth to be sent to the minors. Carrigan later stated that Ruth was not sent down to Providence to make him a better player, but to help the Grays win the International League pennant (league championship).

Ruth joined the Grays on August 18, 1914. What was left of the Baltimore Orioles after Dunn's deals had managed to hold on to first place until August 15, after which they continued to fade, leaving the pennant race between Providence and Rochester. Ruth was deeply impressed by Providence manager "Wild Bill" Donovan, previously a star pitcher with a 25-4 win-loss record for Detroit in 1907; in later years, he credited Donovan with teaching him much about pitching. Ruth was called upon often to pitch, in one stretch starting (and winning) four games in eight days. On September 5 in Toronto, Ruth pitched a one-hit 9-0 victory, and hit his first professional home run, his only one as a minor leaguer, off Ellis Johnson. Recalled to Boston after Providence finished the season in first place, he pitched and won a game for the Red Sox against the New York Yankees on October 2, getting his first major league hit, a double. Ruth finished the season with a record of 2-1 as a major leaguer and 23-8 in the International League (for Baltimore and Providence). Once the season concluded, Ruth married Helen in Ellicott City, Maryland. Creamer speculated that they did not marry in Baltimore, where the newlyweds boarded with George Ruth, Sr., to avoid possible interference from those at St. Mary's—both bride and groom were not yet of age and Ruth remained on parole from that institution until his 21st birthday.

Ruth reported to his first major league spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in March 1915. Despite a relatively successful first season, he was not slated to start regularly for the Red Sox, who had two stellar left-handed pitchers already: the established stars Dutch Leonard, who had broken the record for the lowest earned run average (ERA) in a single season; and Ray Collins, a 20-game winner in both 1913 and 1914. Ruth was ineffective in his first start, taking the loss in the third game of the season. Injuries and ineffective pitching by other Boston pitchers gave Ruth another chance, and after some good relief appearances, Carrigan allowed Ruth another start, and he won a rain-shortened seven inning game. Ten days later, the manager had him start against the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds. Ruth took a 3-2 lead into the ninth, but lost the game 4-3 in 13 innings. Ruth, hitting ninth as was customary for pitchers, hit a massive home run into the upper deck in right field off of Jack Warhop. At the time, home runs were rare in baseball, and Ruth's majestic shot awed the crowd. The winning pitcher, Warhop, would in August 1915 conclude a major league career of eight seasons, undistinguished but for being the first major league pitcher to give up a home run to Babe Ruth.

Carrigan was sufficiently impressed by Ruth's pitching to give him a spot in the starting rotation. Ruth finished the 1915 season 18-8 as a pitcher; as a hitter, he batted .315 and had four home runs. The Red Sox won the AL pennant, but with the pitching staff healthy, Ruth was not called upon to pitch in the 1915 World Series against the Philadelphia Phillies. Boston won in five games; Ruth was used as a pinch hitter in Game Five, but grounded out against Phillies ace Grover Cleveland Alexander. Despite his success as a pitcher, Ruth was acquiring a reputation for long home runs; at Sportsman's Park against the St. Louis Browns, a Ruth hit soared over Grand Avenue, breaking the window of a Chevrolet dealership.

In 1916, there was attention focused on Ruth for his pitching, as he engaged in repeated pitching duels with the ace of the Washington Senators, Walter Johnson. The two met five times during the season, with Ruth winning four and Johnson one (Ruth had a no decision in Johnson's victory). Two of Ruth's victories were by the score of 1-0, one in a 13-inning game. Of the 1-0 shutout decided without extra innings, AL President Ban Johnson stated, "That was one of the best ball games I have ever seen." For the season, Ruth went 23-12, with a 1.75 ERA and nine shutouts, both of which led the league. Ruth's nine shutouts in 1916 set a league record for left-handers that would remain unmatched until Ron Guidry tied it in 1978. The Red Sox won the pennant and World Series again, this time defeating the Brooklyn Superbas (as the Dodgers were then known) in five games. Ruth started and won Game 2, 2-1, in 14 innings. Until another game of that length was played in 2005, this was the longest World Series game, and Ruth's pitching performance is still the longest postseason complete game victory.

Carrigan retired as player and manager after 1916, returning to his native Maine to be a businessman. Ruth, who played under four managers who are in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, always maintained that Carrigan, who is not enshrined there, was the best skipper he ever played for. There were other changes in the Red Sox organization that offseason, as Lannin sold the team to a three-man group headed by New York theatrical promoter Harry Frazee. Jack Barry was hired by Frazee as manager.

Ruth went 24-13 with a 2.01 ERA and six shutouts in 1917, but the Sox finished in second place in the league, nine games behind the Chicago White Sox in the standings. On June 23 at Washington, Ruth made a memorable pitching start. When the home plate umpire called the first four pitches as balls, Ruth threw a punch at him, and was ejected from the game and later suspended for ten days. Ernie Shore was called in to relieve Ruth, and was allowed eight warm-up pitches. The runner who had reached base on the walk was caught stealing, and Shore retired all 26 batters he faced to win the game. Shore's feat was listed as a perfect game for many years; in 1991, Major League Baseball's (MLB) Committee on Statistical Accuracy caused it to be listed as a combined no-hitter. In 1917, Ruth was used little as a batter, other than his plate appearances while pitching, and hit .325 with two home runs.

The entry of the United States into World War I occurred at the start of the season, and overshadowed the sport. Conscription was introduced in September 1917, and most baseball players in the big leagues were of draft age. This included Barry, who was a player-manager, and who joined the Naval Reserve in an attempt to avoid the draft, only to be called up after the 1917 season. Frazee hired International League President Ed Barrow as Red Sox manager. Barrow had spent the previous 30 years in a variety of baseball jobs, though he never played the game professionally. With the major leagues shorthanded due to the war, Barrow had many holes in the Red Sox lineup to fill.

Ruth also noticed these vacancies in the lineup, and, dissatisfied in the role of a pitcher who appeared every four or five days, wanted to play every day at another position. Barrow tried Ruth at first base and in the outfield during the exhibition season, but as the team moved towards Boston and the season opener, restricted him to pitching. At the time, Ruth was possibly the best left-handed pitcher in baseball; allowing him to play another position was an experiment that could have backfired.

Inexperienced as a manager, Barrow had player Harry Hooper advise him on baseball game strategy. Hooper urged his manager to allow Ruth to play another position when he was not pitching, arguing to Barrow, who had invested in the club, that the crowds were larger on days when Ruth played, as they were attracted by his hitting. Barrow gave in early in May; Ruth promptly hit home runs in four consecutive games (one an exhibition), the last off of Walter Johnson. For the first time in his career (disregarding pinch-hitting appearances), Ruth was allowed a place in the batting order higher than ninth.

Although Barrow predicted that Ruth would beg to return to pitching the first time he experienced a batting slump, that did not occur. Barrow used Ruth primarily as an outfielder in the war-shortened 1918 season. Ruth hit .300, with 11 home runs, enough to secure him a share of the major league home run title with Tillie Walker of the Philadelphia Athletics. He was still occasionally used as a pitcher, and had a 13-7 record with a 2.22 ERA.

The Red Sox won their third pennant in four years, and faced the Chicago Cubs in the 1918 World Series, beginning on September 5, the earliest in history. The season was shortened as the government had ruled that baseball players eligible for the military would have to be inducted or work in critical war industries, such as armaments plants. Ruth pitched Game One for the Red Sox, a 1-0 shutout. Before Game Four, Ruth injured his left hand in a fight; he pitched anyway. He gave up seven hits and six walks, but was helped by outstanding fielding behind him and by his own batting efforts, as a fourth-inning triple by Ruth gave his team a 2-0 lead. The Cubs tied the game in the eighth inning, but the Red Sox scored to take a 3-2 again in the bottom of that inning. After Ruth gave up a hit and a walk to start the ninth inning, he was relieved on the mound by Joe Bush. To keep Ruth and his bat in the game, he was sent to play left field. Bush retired the side to give Ruth his second win of the Series, and the third and last World Series pitching victory of his career, against no defeats, in three pitching appearances. Ruth's effort gave his team a three-games-to-one lead, and two days later the Red Sox won their third Series in four years, four games to two. Before allowing the Cubs to score in Game Four, Ruth pitched 29 2⁄3 consecutive scoreless innings, a record for the World Series that stood for more than 40 years until 1961, broken by Whitey Ford after Ruth's death. Ruth was prouder of that record than he was of any of his batting feats.

With the World Series over, Ruth gained exemption from the war draft by accepting a nominal position with a Pennsylvania steel mill. Many industrial establishments took pride in their baseball teams and sought to hire major leaguers. The end of the war in November set Ruth free to play baseball without such contrivances.

During the 1919 season, Ruth pitched in only 17 of his 130 games, compiling an 8-5 record as Barrow used him as a pitcher mostly in the early part of the season, when the Red Sox manager still had hopes of a second consecutive pennant. By late June, the Red Sox were clearly out of the race, and Barrow had no objection to Ruth concentrating on his hitting, if only because it drew people to the ballpark. Ruth had hit a home run against the Yankees on Opening Day, and another during a month-long batting slump that soon followed. Relieved of his pitching duties, Ruth began an unprecedented spell of slugging home runs, which gave him widespread public and press attention. Even his failures were seen as majestic—one sportswriter noted, "When Ruth misses a swipe at the ball, the stands quiver".

Two home runs by Ruth on July 5, and one in each of two consecutive games a week later, raised his season total to 11, tying his career best from 1918. The first record to fall was the AL single-season mark of 16, set by Ralph "Socks" Seybold in 1902. Ruth matched that on July 29, then pulled ahead toward the major league record of 24, set by Buck Freeman in 1899. Ruth reached this on September 8, by which time, writers had discovered that Ned Williamson of the 1884 Chicago White Stockings had hit 27—though in a ballpark where the distance to right field was only 215 feet (66 m). On September 20, "Babe Ruth Day" at Fenway Park, Ruth won the game with a home run in the bottom of the ninth inning, tying Williamson. He broke the record four days later against the Yankees at the Polo Grounds, and hit one more against the Senators to finish with 29. The home run at Washington made Ruth the first major league player to hit a home run at all eight ballparks in his league. In spite of Ruth's hitting heroics, the Red Sox finished sixth, 20 1⁄2 games behind the league champion White Sox.

As an out-of-towner from New York City, Frazee had been regarded with suspicion by Boston's sportswriters and baseball fans when he bought the team. He won them over with success on the field and a willingness to build the Red Sox by purchasing or trading for players. He offered the Senators $60,000 for Walter Johnson, but Washington owner Clark Griffith was unwilling. Even so, Frazee was successful in bringing other players to Boston, especially as replacements for players in the military. This willingness to spend for players helped the Red Sox secure the 1918 title. The 1919 season saw record-breaking attendance, and Ruth's home runs for Boston made him a national sensation. Nevertheless, on December 26, 1919, Frazee sold Ruth's contract to the New York Yankees.

Not all of the circumstances concerning the sale are known, but brewer and former congressman Jacob Ruppert, the New York team's principal owner, reportedly asked Yankee manager Miller Huggins what the team needed to be successful. "Get Ruth from Boston", Huggins supposedly replied, noting that Frazee was perennially in need of money to finance his theatrical productions. In any event, there was precedent for the Ruth transaction: when Boston pitcher Carl Mays left the Red Sox in a 1919 dispute, Frazee had settled the matter by selling Mays to the Yankees, though over the opposition of AL President Johnson.

According to one of Ruth's biographers, Jim Reisler, "why Frazee needed cash in 1919—and large infusions of it quickly—is still, more than 80 years later, a bit of a mystery". The often-told story is that Frazee needed money to finance the musical No, No, Nanette, which was a Broadway hit and brought Frazee financial security. That play did not open until 1925, however, by which time Frazee had sold the Red Sox. Still, the story may be true in essence: No, No, Nanette was based on a Frazee-produced play, My Lady Friends, which opened in 1919.

There were other financial pressures on Frazee, despite his team's success. Ruth, fully aware of baseball's popularity and his role in it, wanted to renegotiate his contract, signed before the 1919 season for $10,000 per year through 1921. He demanded that his salary be doubled, or he would sit out the season and cash in on his popularity through other ventures. Ruth's salary demands were causing other players to ask for more money. Additionally, Frazee still owed Lannin as much as $125,000 from the purchase of the club.

Although Ruppert and his co-owner, Colonel Tillinghast Huston, were both wealthy, and had aggressively purchased and traded for players in 1918 and 1919 to build a winning team, Ruppert faced losses in his brewing interests as Prohibition was implemented, and if their team left the Polo Grounds, where the Yankees were the tenants of the New York Giants, building a stadium in New York would be expensive. Nevertheless, when Frazee, who moved in the same social circles as Huston, hinted to the colonel that Ruth was available for the right price, the Yankees owners quickly pursued the purchase.

Frazee sold the rights to Babe Ruth for $100,000, the largest sum ever paid for a baseball player. The deal also involved a $350,000 loan from Ruppert to Frazee, secured by a mortgage on Fenway Park. Once it was agreed, Frazee informed Barrow, who, stunned, told the owner that he was getting the worse end of the bargain. Cynics have suggested that Barrow may have played a larger role in the Ruth sale, as less than a year after, he became the Yankee general manager, and in the following years made a number of purchases of Red Sox players from Frazee. The $100,000 price included $25,000 in cash, and notes for the same amount due November 1 in 1920, 1921, and 1922; Ruppert and Huston assisted Frazee in selling the notes to banks for immediate cash.

The transaction was contingent on Ruth signing a new contract, which was quickly accomplished—Ruth agreed to fulfill the remaining two years on his contract, but was given a $20,000 bonus, payable over two seasons. The deal was announced on January 6, 1920. Reaction in Boston was mixed: some fans were embittered at the loss of Ruth; others conceded that the slugger had become difficult to deal with. The New York Times suggested presciently, "The short right field wall at the Polo Grounds should prove an easy target for Ruth next season and, playing seventy-seven games at home, it would not be surprising if Ruth surpassed his home run record of twenty-nine circuit clouts next Summer." According to Reisler, "The Yankees had pulled off the sports steal of the century."

According to Marty Appel in his history of the Yankees, the transaction, "changed the fortunes of two high-profile franchises for decades". The Red Sox, winners of five of the first sixteen World Series, those played between 1903 and 1919, would not win another pennant until 1946, or another World Series until 2004, a drought attributed in baseball superstition to Frazee's sale of Ruth and sometimes dubbed the "Curse of the Bambino". The Yankees, on the other hand, had not won the AL championship prior to their acquisition of Ruth. They won seven AL pennants and four World Series with Ruth, and lead baseball with 40 pennants and 27 World Series titles in their history.

As a Yankee, Ruth's transition from a pitcher to a power-hitting outfielder became complete. In his fifteen-season Yankee career, consisting of over 2,000 games, Ruth broke many batting records, while making only five widely scattered appearances on the mound, winning all of them.

At the end of April 1920, the Yankees were 4-7, with the Red Sox leading the league with a 10-2 mark. Ruth had done little, having injured himself swinging the bat. Both situations began to change on May 1, when Ruth hit a ball completely out of the Polo Grounds, a feat believed only to have been previously accomplished by Shoeless Joe Jackson. The Yankees won, 6-0, taking three out of four from the Red Sox. Ruth hit his second home run on May 2, and by the end of the month had set a major league record for home runs in a month with 11, and promptly broke it with 13 in June. Fans responded with record attendance: on May 16, Ruth and the Yankees drew 38,600 to the Polo Grounds, a record for the ballpark, and 15,000 fans were turned away. Large crowds jammed stadiums to see Ruth play when the Yankees were on the road.

The home runs kept coming; Ruth tied his own record of 29 on July 15, and broke it with home runs in both games of a doubleheader four days later. By the end of July, he had 37, but his pace slackened somewhat after that. Nevertheless, on September 4, he both tied and broke the organized baseball record for home runs in a season, snapping Perry Werden's 1895 mark of 44 in the minor Western League. The Yankees played well as a team, battling for the league lead early in the summer, but slumped in August in the AL pennant battle with Chicago and Cleveland. The championship was won by Cleveland, surging ahead after the Black Sox Scandal broke on September 28 and led to the suspension of many of the team's top players, including Joe Jackson. The Yankees finished third, but drew 1.2 million fans to the Polo Grounds, the first time a team had drawn a seven figure attendance. The rest of the league sold 600,000 more tickets, many fans there to see Ruth, who led the league with 54 home runs, 158 runs, and 137 runs batted in (RBIs).

Ruth was aided in his exploits, in 1920 and afterwards, by the fact that the A.J. Reach Company, maker of baseballs used in the major leagues, was using a more efficient machine to wind the yarn found within the baseball. When these went into play in 1920, the start of the live-ball era, the number of home runs increased by 184 over the previous year across the major leagues. Baseball statistician Bill James points out that while Ruth was likely aided by the change in the baseball, there were other factors at work, including the gradual abolition of the spitball (accelerated after the death of Ray Chapman, struck by a pitched ball thrown by Mays in August 1920) and the more frequent use of new baseballs (also a response to Chapman's death). Nevertheless, James theorizes that Ruth's 1920 explosion might have happened in 1919, had a full season of 154 games been played rather than 140, had Ruth refrained from pitching 133 innings that season, and if he were playing with any other home field but Fenway Park, where he hit only 9 of 29 home runs.

Yankees business manager Harry Sparrow had died early in the 1920 season; to replace him, Ruppert and Huston hired Barrow. Ruppert and Barrow quickly made a deal with Frazee for New York to acquire some of the players who would be mainstays of the early Yankee pennant-winning teams, including catcher Wally Schang and pitcher Waite Hoyt. The 21-year-old Hoyt became close to Ruth:

The outrageous life fascinated Hoyt, the don't-give-a-shit freedom of it, the nonstop, pell-mell charge into excess. How did a man drink so much and never get drunk? ... The puzzle of Babe Ruth never was dull, no matter how many times Hoyt picked up the pieces and stared at them. After games he would follow the crowd to the Babe's suite. No matter what the town, the beer would be iced and the bottles would fill the bathtub.

Ruth hit home runs early and often in the 1921 season, during which he broke Roger Connor's mark for home runs in a career, 138. Each of the almost 600 home runs Ruth hit in his career after that extended his own record. After a slow start, the Yankees were soon locked in a tight pennant race with Cleveland, winners of the 1920 World Series. On September 15, Ruth hit his 55th home run, shattering his year-old single season record. In late September, the Yankees visited Cleveland and won three out of four games, giving them the upper hand in the race, and clinched their first pennant a few days later. Ruth finished the regular season with 59 home runs, batting .378 and with a slugging percentage of .846.

The Yankees had high expectations when they met the New York Giants in the 1921 World Series, and the Yankees won the first two games with Ruth in the lineup. However, Ruth badly scraped his elbow during Game 2, sliding into third base (he had walked and stolen both second and third bases). After the game, he was told by the team physician not to play the rest of the series. Despite this advice, he did play in the next three games, and pinch-hit in Game Eight of the best-of-nine series, but the Yankees lost, five games to three. Ruth hit .316, drove in five runs and hit his first World Series home run.

After the Series, Ruth and teammates Bob Meusel and Bill Piercy participated in a barnstorming tour in the Northeast. A rule then in force prohibited World Series participants from playing in exhibition games during the offseason, the purpose being to prevent Series participants from replicating the Series and undermining its value. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis suspended the trio until May 20, 1922, and fined them their 1921 World Series checks. In August 1922, the rule was changed to allow limited barnstorming for World Series participants, with Landis's permission required.

On March 6, 1922, Ruth signed a new contract, for three years at $52,000 a year. The largest sum ever paid a ballplayer to that point, it represented 40% of the team's player payroll. Despite his suspension, Ruth was named the Yankees' new on-field captain prior to the 1922 season. During the suspension, he worked out with the team in the morning, and played exhibition games with the Yankees on their off days. He and Meusel returned on May 20, to a sellout crowd at the Polo Grounds, but Ruth batted 0-for-4, and was booed. On May 25, he was thrown out of the game for throwing dust in umpire George Hildebrand's face, then climbed into the stands to confront a heckler. Ban Johnson ordered him fined, suspended, and stripped of his captaincy. In his shortened season, Ruth appeared in 110 games, batted .315, with 35 home runs, and drove in 99 runs, but compared to his previous two dominating years, the 1922 season was a disappointment. Despite Ruth's off-year, Yankees managed to win the pennant to face the New York Giants for the second straight year in the World Series. In the Series, Giants manager John McGraw instructed his pitchers to throw him nothing but curveballs, and Ruth never adjusted. Ruth had just two hits in seventeen at bats, and the Yankees lost to the Giants for the second straight year, by 4-0 (with one tie game). Sportswriter Joe Vila called him, "an exploded phenomenon".

After the season, Ruth was a guest at an Elks Club banquet, set up by Ruth's agent with Yankee team support. There, each speaker, concluding with future New York mayor Jimmy Walker, censured him for his poor behavior. An emotional Ruth promised reform, and, to the surprise of many, followed through. When he reported to spring training, he was in his best shape as a Yankee, weighing only 210 pounds (95 kg).

The Yankees's status as tenants of the Giants at the Polo Grounds had become increasingly uneasy, and in 1922 Giants owner Charles Stoneham stated that the Yankees's lease, expiring after that season, would not be renewed. Ruppert and Huston had long contemplated a new stadium, and had taken an option on property at 161st Street and River Avenue in the Bronx. Yankee Stadium was completed in time for the home opener on April 18, 1923, at which the Babe hit the first home run in what was quickly dubbed "the House that Ruth Built". The ballpark was designed with Ruth in mind: although the venue's left-field fence was further from home plate than at the Polo Grounds, Yankee Stadium's right-field fence was closer, making home runs easier to hit for left-handed batters. To spare Ruth's eyes, right field-his defensive position-was not pointed into the afternoon sun, as was traditional; left fielder Meusel was soon suffering headaches from squinting toward home plate.

The Yankees were never challenged, leading the league for most of the 1923 season and winning the AL pennant by 17 games. Ruth finished the season with a career-high .393 batting average and major-league leading 41 home runs (tied with Cy Williams). Another career high for Ruth in 1923 was his 45 doubles, and he reached base 379 times, then a major league record. For the third straight year, the Yankees faced the Giants in the World Series, which Ruth dominated. He batted .368, walked eight times, scored eight runs, hit three home runs and slugged 1.000 during the series, as the Yankees won their first World Series championship, four games to two.

In 1924, the Yankees were favored to become the first team to win four consecutive pennants. Plagued by injuries, they found themselves in a battle with the Senators. Although the Yankees won 18 of 22 at one point in September, the Senators beat out the Yankees by two games. Ruth hit .378, winning his only AL batting title, with a league-leading 46 home runs.

Ruth had kept up his efforts to stay in shape in 1923 and 1924, but by early 1925 weighed nearly 260 pounds (120 kg). His annual visit to Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he exercised and took saunas early in the year, did him no good as he spent much of the time carousing in the resort town. He became ill while there, and suffered relapses during spring training. Ruth collapsed in Asheville, North Carolina, as the team journeyed north. He was put on a train for New York, where he was briefly hospitalized. A rumor circulated that he had died, prompting British newspapers to print a premature obituary. In New York, Ruth collapsed again and was found unconscious in his hotel bathroom. He was taken to a hospital where he suffered multiple convulsions. After sportswriter W. O. McGeehan wrote that Ruth's illness was due to binging on hot dogs and soda pop before a game, it became known as "the bellyache heard 'round the world". However, the exact cause of his ailment has never been confirmed and remains a mystery. Glenn Stout, in his history of the Yankees, notes that the Ruth legend is "still one of the most sheltered in sports"; he suggests that alcohol was at the root of Ruth's illness, pointing to the fact that Ruth remained six weeks at St. Vincent's Hospital but was allowed to leave, under supervision, for workouts with the team for part of that time. He concludes that the hospitalization was behavior-related. Playing just 98 games, Ruth had his worst season as a Yankee; he finished with a .290 average and 25 home runs. The Yankees finished next to last in the AL with a 69-85 record, their last season with a losing record until 1965.

Ruth spent part of the offseason of 1925-26 working out at Artie McGovern's gym, getting back into shape. Barrow and Huggins had rebuilt the team, surrounding the veteran core with good young players like Tony Lazzeri and Lou Gehrig. But New York was not expected to win the pennant.

Babe Ruth returned to his normal production during 1926, batting .372 with 47 home runs and 146 RBIs. The Yankees built a ten-game lead by mid-June, and coasted to win the pennant by three games. The St. Louis Cardinals had won the National League with the lowest winning percentage for a pennant winner to that point (.578) and the Yankees were expected to win the World Series easily. Although the Yankees won the opener in New York, St. Louis took Games Two and Three. In Game Four, Ruth hit three home runs, the first time this had been done in a World Series game, to lead the Yankees to victory; in the fifth game Ruth caught a ball as he crashed into the fence, described by baseball writers as a defensive gem. New York took that game, but Grover Cleveland Alexander won Game Six for St. Louis to tie the Series at three games each, then got very drunk. He was nevertheless inserted into Game Seven in the seventh inning and shut down the Yankees to win the game, 3-2, and win the Series. Ruth had hit his fourth home run of the Series earlier in the game, and was the only Yankee to reach base off Alexander, walking in the ninth inning before being caught stealing to end the game. Although Ruth's attempt to steal second is often deemed a baserunning blunder, Creamer pointed out that the Yankees' chances of tying the game would have been greatly improved with a runner in scoring position.

The 1926 Series was also known for Ruth's promise to Johnny Sylvester, a hospitalized 11-year-old, that he would hit a home run on his behalf. Sylvester had been injured in a fall from a horse, and a friend of Sylvester's father gave the boy two autographed baseballs signed by Yankees and Cardinals, and relayed a promise from Ruth, who did not know the boy, to hit a home run for him. After the Series, Ruth visited the boy in the hospital. When the matter became public, the press greatly inflated it, and by some accounts, Ruth saved a dying boy's life by visiting him, emotionally promising to hit a home run, and doing so.

The 1927 New York Yankees team is considered one of the greatest squads that ever took the field. Known as Murderer's Row because of the power of its lineup, the team won a then-AL-record 110 games, and took the AL pennant by 19 games, clinching first place on Labor Day. With little suspense as to the pennant race, the nation's attention turned to Ruth's pursuit of his own single-season home run record of 59. He was not alone in this chase: Gehrig proved to be a slugger capable of challenging Ruth for his home run crown, tying Ruth with 24 home runs late in June. Through July and August, they were never separated by more than two home runs. Gehrig took the lead, 45-44, in the first game of a doubleheader at Fenway Park early in September; Ruth responded with two of his own to take the lead, as it proved permanently—Gehrig finished with 47. Even so, as of September 6, Ruth was still several games off his 1921 pace, and going into the final series against the Senators, had only 57. He hit two in the first game of the series, including one off of Paul Hopkins, facing his first major league batter, to tie the record. The following day, September 30, he broke it with his 60th homer, in the eighth inning off Tom Zachary to break a 2-2 tie. "Sixty! Let's see some son of a bitch try to top that one", Ruth exulted after the game. In addition to his career-high 60 home runs, Ruth batted .356, drove in 164 runs and slugged .772. In the 1927 World Series, the Yankees swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in four games; the National Leaguers were disheartened after watching the Yankees take batting practice before Game One, with ball after ball leaving Forbes Field. According to Appel, "The 1927 New York Yankees. Even today, the words inspire awe ... all baseball success is measured against the '27 team."

Before the 1928 season, Ruth signed a new contract for an unprecedented $80,000 per year. The season started off well for the Yankees, who led the league in the early going. But the Yankees were plagued by injuries, erratic pitching and inconsistent play. The Philadelphia Athletics, rebuilding after some lean years, erased the Yankees' big lead and even took over first place briefly in early September. The Yankees, however, regained first place when they beat the Athletics three out of four games in a pivotal series at Yankee Stadium later that month, and clinched the pennant in the final weekend of the season. Ruth's play in 1928 mirrored his team's performance. He got off to a hot start and on August 1, he had 42 home runs. This put him ahead of his 60 home run pace from the previous season. He then slumped for the latter part of the season, and he hit just twelve home runs in the last two months. Ruth's batting average also fell to .323, well below his career average. Nevertheless, he ended the season with 54 home runs. The Yankees swept the favored Cardinals in four games in the World Series, with Ruth batting .625 and hitting three home runs in Game Four, including one off Alexander.

Before the 1929 season, Ruppert, who had bought out Huston in 1923, announced that the Yankees would wear uniform numbers to allow fans at cavernous Yankee Stadium to tell one player from another. The Cardinals and Indians had each experimented with uniform numbers; the Yankees were the first to use them on both home and away uniforms. As Ruth batted third, he was given number 3. According to a long-standing baseball legend, the Yankees adopted their now-iconic pinstriped uniforms in hopes of making Ruth look slimmer. In truth, though, they had been wearing pinstripes since Ruppert bought the team in 1915.

Although the Yankees started well, the Athletics soon proved they were the better team in 1929, splitting two series with the Yankees in the first month of the season, then taking advantage of a Yankee losing streak in mid-May to gain first place. Although Ruth performed well, the Yankees were not able to catch the Athletics—Connie Mack had built another great team. Tragedy struck the Yankees late in the year as manager Huggins died of erysipelas, a bacterial skin infection, on September 25, only ten days after he had last led the team. Despite past differences, Ruth praised Huggins and described him as a "great guy". The Yankees finished second, 18 games behind the Athletics. Ruth hit .345 during the season, with 46 home runs and 154 RBIs.

The Yankees hired Bob Shawkey as manager, their fourth choice. Ruth politicked for the job of player-manager, but was not seriously considered by Ruppert and Barrow; Stout deems this the first hint Ruth would have no future with the Yankees once he was done as a player. Shawkey, a former Yankees player and teammate of Ruth, was unable to command the slugger's respect. The Athletics won their second consecutive pennant and World Series, as the Yankees finished in third place, sixteen games back. During that season Ruth was asked by a reporter what he thought of his yearly salary of $80,000 being more than President Hoover's $75,000. His response was, "I know, but I had a better year than Hoover." In 1930, Ruth hit .359 with 49 home runs (his best in his years after 1928) and 153 RBIs, and pitched his first game in nine years, a complete game victory. At the end of the season, Shawkey was fired and replaced with Cubs manager Joe McCarthy, though Ruth again unsuccessfully sought the job.

McCarthy was a disciplinarian, but chose not to interfere with Ruth, and the slugger for his part did not seek conflict with the manager. The team improved in 1931, but was no match for the Athletics, who won 107 games, 13 1⁄2 games in front of the Yankees. Ruth, for his part, hit .373, with 46 home runs and 163 RBIs. He had 31 doubles, his most since 1924. In the 1932 season, the Yankees went 107-47 and won the pennant. Ruth's effectiveness had decreased somewhat, but he still hit .341 with 41 home runs and 137 RBIs. Nevertheless, he twice was sidelined due to injury during the season.

The Yankees faced the Cubs, McCarthy's former team, in the 1932 World Series. There was bad blood between the two teams as the Yankees resented the Cubs only awarding half a World Series share to Mark Koenig, a former Yankee. The games at Yankee Stadium had not been sellouts; both were won by the home team, with Ruth collecting two singles, but scoring four runs as he was walked four times by the Cubs pitchers. In Chicago, Ruth was resentful at the hostile crowds that met the Yankees's train and jeered them at the hotel. The crowd for Game Three included New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democratic candidate for president, who sat with Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak. Many in the crowd threw lemons at Ruth, a sign of derision, and others (as well as the Cubs themselves) shouted abuse at Ruth and other Yankees. They were briefly silenced when Ruth hit a three-run home run off Charlie Root in the first inning, but soon revived, and the Cubs tied the score at 4-4 in the fourth inning. When Ruth came to the plate in the top of the fifth, the Chicago crowd and players, led by pitcher Guy Bush, were screaming insults at Ruth. With the count at two balls and one strike, Ruth gestured, possibly in the direction of center field, and after the next pitch (a strike), may have pointed there with one hand. Ruth hit the fifth pitch over the center field fence; estimates were that it traveled nearly 500 feet (150 m). Whether or not Ruth intended to indicate where he planned to (and did) hit the ball, the incident has gone down in legend as Babe Ruth's called shot. The Yankees won Game Three, and the following day clinched the Series with another victory. During that game, Bush hit Ruth on the arm with a pitch, causing words to be exchanged and provoking a game-winning Yankee rally.

Ruth remained productive in 1933, as he batted .301, with 34 home runs, 103 RBIs, and a league-leading 114 walks, as the Yankees finished second, seven games behind the Senators. He was selected to play right field by Athletics manager Connie Mack in the first Major League Baseball All-Star Game, held on July 6, 1933, at Comiskey Park in Chicago. He hit the first home run in the All-Star Game's history, a two-run blast against Bill Hallahan during the third inning, which helped the AL win the game 4-2. During the final game of the 1933 season, as a publicity stunt organized by his team, Ruth was called upon and pitched a complete game victory against the Red Sox, his final appearance as a pitcher. Despite unremarkable pitching numbers, Ruth had a 5-0 record in five games for the Yankees, raising his career totals to 94-46.

In 1934, Ruth played in his last full season. By this time, years of high living were starting to catch up with him. His conditioning had deteriorated to the point that he could no longer field or run. He accepted a pay cut from Ruppert to $35,000, but was still the highest-paid player in the major leagues. He could still handle a bat, recording a .288 batting average with 22 home runs, statistics Reisler described as "merely mortal". Ruth was selected to the AL All-Star team for the second consecutive year. During the game, New York Giants pitcher Carl Hubbell struck out Ruth and four other future Hall-of-Famers consecutively. The Yankees finished second again, seven games behind the Tigers.

Although Ruth knew he was nearly finished as a player, he desired to remain in baseball as a manager. He was often spoken of as a possible candidate as managerial jobs opened up, but in 1932, when he was mentioned as a contender for the Red Sox position, Ruth stated that he was not yet ready to leave the field. There were rumors that Ruth was a likely candidate each time when the Cleveland Indians, Cincinnati Reds, and Detroit Tigers were looking for a manager, but nothing came of them.

Just before the 1934 season, Ruppert offered to make Ruth the manager of the Yankees' top minor-league team, the Newark Bears, but he was talked out of it by his wife, Claire, and his business manager, Christy Walsh. Shortly afterward, Tigers owner Frank Navin made a proposal to Ruppert and Barrow—if the Yankees traded Ruth to Detroit, Navin would name Ruth player-manager. Navin believed Ruth would not only bring a winning attitude to a team that had not finished higher than third since 1923, but would also revive the Tigers' sagging attendance figures. Navin asked Ruth to come to Detroit for an interview. However, Ruth balked, since Walsh had already arranged for him to take part in a celebrity golf tournament in Hawaii. Ruth and Navin negotiated over the phone while Ruth was in Hawaii, but those talks foundered when Navin refused to give Ruth a portion of the Tigers' box office proceeds.

Early in the 1934 season, Ruth began openly campaigning to become manager of the Yankees. However, the Yankee job was never a serious possibility. Ruppert always supported McCarthy, who would remain in his position for another 12 seasons. Ruth and McCarthy's relationship had been lukewarm at best, and Ruth's managerial ambitions further chilled their relations. By the end of the season, Ruth hinted that he would retire unless Ruppert named him manager of the Yankees. For his part, Ruppert wanted his slugger to leave the team without drama and hard feelings when the time came.

During the 1934-35 offseason, Ruth circled the world with his wife, including a barnstorming tour of the Far East. At his final stop before returning home, in the United Kingdom, Ruth was introduced to cricket by Australian player Alan Fairfax, and after having little luck in a cricketer's stance, stood as a baseball batter and launched some massive shots around the field, destroying the bat in the process. Although Fairfax regretted that he could not have the time to make Ruth a cricket player, Ruth had lost any interest in such a career upon learning that the best batsmen made only about $40 per week.

Also during the offseason, Ruppert had been sounding out the other clubs in hopes of finding one that would be willing to take Ruth as a manager and/or a player. However, the only serious offer came from Athletics owner-manager Connie Mack, who gave some thought to stepping down as manager in favor of Ruth. However, Mack later dropped the idea, saying that Ruth's wife would be running the team in a month if Ruth ever took over.

While the barnstorming tour was under way, Ruppert began negotiating with Boston Braves owner Judge Emil Fuchs, who wanted Ruth as a gate attraction. Although the Braves had enjoyed modest recent success, finishing fourth in the National League in both 1933 and 1934, the team performed poorly at the box office. Unable to afford the rent at Braves Field, Fuchs had considered holding dog races there when the Braves were not at home, only to be turned down by Landis. After a series of phone calls, letters, and meetings, the Yankees traded Ruth to the Braves on February 26, 1935. Ruppert had stated that he would not release Ruth to go to another team as a full-time player. For this reason, it was announced that Ruth would become a team vice president and would be consulted on all club transactions, in addition to playing. He was also made assistant manager to Braves skipper Bill McKechnie. In a long letter to Ruth a few days before the press conference, Fuchs promised Ruth a share in the Braves' profits, with the possibility of becoming co-owner of the team. Fuchs also raised the possibility of Ruth succeeding McKechnie as manager, perhaps as early as 1936. Ruppert called the deal "the greatest opportunity Ruth ever had".

There was considerable attention as Ruth reported for spring training. He did not hit his first home run of the spring until after the team had left Florida, and was beginning the road north in Savannah. He hit two in an exhibition against the Bears. Amid much press attention, Ruth played his first home game in Boston in over 16 years. Before an opening-day crowd of over 25,000, including five of New England's six state governors, Ruth accounted for all of the Braves' runs in a 4-2 defeat of the New York Giants, hitting a two-run home run, singling to drive in a third run and later in the inning scoring the fourth. Although age and weight had slowed him, he made a running catch in left field that sportswriters deemed the defensive highlight of the game.

Ruth had two hits in the second game of the season, but it quickly went downhill both for him and the Braves from there. The season soon settled down to a routine of Ruth performing poorly on the few occasions he even played at all, and the Braves losing most games. As April passed into May, Ruth's deterioration became even more pronounced. While he remained productive at the plate early on, he could do little else. His condition had deteriorated to the point that he could barely trot around the bases. His fielding had become so poor that three Braves pitchers told McKechnie that they would not take the mound if he was in the lineup. Before long, Ruth stopped hitting as well. He grew increasingly annoyed that McKechnie ignored most of his advice. For his part, McKechnie later said that Ruth's huge salary and refusal to stay with the team while on the road made it nearly impossible to enforce discipline.

Ruth soon realized that Fuchs had deceived him, and had no intention of making him manager or giving him any significant off-field duties. He later stated that his only duties as vice president consisted of making public appearances and autographing tickets. Ruth also found out that far from giving him a share of the profits, Fuchs wanted him to invest some of his money in the team in a last-ditch effort to improve its balance sheet. As it turned out, both Fuchs and Ruppert had known all along that Ruth's non-playing positions were meaningless.

By the end of the first month of the season, Ruth concluded he was finished even as a part-time player. As early as May 12, he asked Fuchs to let him retire. Ultimately, Fuchs persuaded Ruth to remain at least until after the Memorial Day doubleheader in Philadelphia. In the interim was a western road trip, at which the rival teams had scheduled days to honor him. In Chicago and St. Louis, Ruth performed poorly, and his batting average sank to .155, with only three home runs. In the first two games in Pittsburgh, Ruth had only one hit, though a long fly caught by Paul Waner probably would have been a home run in any other ballpark besides Forbes Field.

Ruth played in the third game of the Pittsburgh series on May 25, 1935, and added one more tale to his playing legend. Ruth went 4-for-4, including three home runs, though the Braves lost the game 11-7. The last two were off Ruth's old Cubs nemesis, Guy Bush. The final home run, both of the game and of Ruth's career, sailed over the upper deck in right field and out of the ballpark, the first time anyone had hit a fair ball completely out of Forbes Field. Ruth was urged to make this his last game, but he had given his word to Fuchs and played in Cincinnati and Philadelphia. The first game of the doubleheader in Philadelphia—the Braves lost both—was his final major league appearance. On June 2, after an argument with Fuchs, Ruth retired. He finished 1935 with a .181 average—easily his worst as a full-time position player—and the final six of his 714 home runs. The Braves, 10-27 when Ruth left, finished 38-115, at .248 the worst winning percentage in modern National League history. Insolvent like his team, Fuchs gave up control of the Braves before the end of the season; the National League took over the franchise at the end of the year.

Although Fuchs had given Ruth his unconditional release, no major league team expressed an interest in hiring him in any capacity. Ruth still hoped to be hired as a manager if he could not play anymore, but only one managerial position, Cleveland, became available between Ruth's retirement and the end of the 1937 season. Asked if he had considered Ruth for the job, Indians owner Alva Bradley replied negatively.

The writer Creamer believed Ruth was unfairly treated in never being given an opportunity to manage a major league club. The author believed there was not necessarily a relationship between personal conduct and managerial success, noting that McGraw, Billy Martin, and Bobby Valentine were winners despite character flaws. Team owners and general managers assessed Ruth's flamboyant personal habits as a reason to exclude him from a managerial job; Barrow said of him, "How can he manage other men when he can't even manage himself?"

Ruth played much golf and in a few exhibition baseball games, demonstrating a continuing ability to draw large crowds. This appeal contributed to the Dodgers hiring him as first base coach in 1938. But Brooklyn general manager Larry MacPhail made it clear when Ruth was hired that he would not be considered for the manager's job if, as expected, Burleigh Grimes retired at the end of the season. Although much was said about what Ruth could teach the younger players, in practice, his duties were to appear on the field in uniform and encourage base runners—he was not called upon to relay signs. He got along well with everyone except team captain Leo Durocher, who was hired as Grimes' replacement at season's end. Ruth returned to retirement, never again to work in baseball.

On July 4, 1939, Ruth spoke on Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day at Yankee Stadium as members of the 1927 Yankees and a sellout crowd turned out to honor the first baseman, forced into premature retirement by ALS disease, which would kill him in two years. The next week, Ruth went to Cooperstown, New York, for the formal opening of the Baseball Hall of Fame. Three years earlier he was one of the first five players elected to it. As radio broadcasts of baseball became popular, Ruth sought a job in that field, arguing that his celebrity and knowledge of baseball would assure large audiences, but he received no offers. During World War II, he made many personal appearances to advance the war effort, including his last appearance as a player at Yankee Stadium, in a 1943 exhibition for the Army-Navy Relief Fund. He hit a long fly ball off Walter Johnson; the blast left the field, curving foul, but Ruth circled the bases anyway. In 1946, he made a final effort to gain a job in baseball, contacting new Yankees boss MacPhail, but was sent a rejection letter.

Ruth met Helen Woodford (1897-1929), by some accounts, in a coffee shop in Boston where she was a waitress, and they were married on October 17, 1914; he was 19 and she was 17. They adopted a daughter, Dorothy (1921-1989), in 1921. Ruth and Helen separated around 1925, reportedly due to his repeated infidelities. Their last public appearance together came during the 1926 World Series. Helen died in January 1929 at age 31 in a house fire in Watertown, Massachusetts, in a house owned by Edward Kinder, a dentist with whom she had been living as "Mrs. Kinder". In her book, My Dad, the Babe, Dorothy claimed that she was Ruth's biological child by a mistress named Juanita Jennings. She died in 1989.

On April 17, 1929, only three months after the death of his first wife, Ruth married actress and model Claire Merritt Hodgson (1897-1976) and adopted her daughter Julia; he was 34 and she was 31. It was the second and final marriage for both parties. By one account, Julia and Dorothy were, through no fault of their own, the reason for the seven-year rift in Ruth's relationship with teammate Lou Gehrig. Sometime in 1932, Gehrig's mother, during a conversation which she assumed was private, remarked, "It's a shame doesn't dress Dorothy as nicely as she dresses her own daughter." When the comment inevitably got back to Ruth, he angrily told Gehrig to tell his mother to mind her own business. Gehrig in turn took offense at what he perceived as Ruth's comment about his mother. The two men reportedly never spoke off the field until they reconciled at Yankee Stadium on Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day in 1939.

Although Ruth was married through most of his baseball career, when Colonel Huston asked him to tone down his lifestyle, the player said, "I'll promise to go easier on drinking and to get to bed earlier, but not for you, fifty thousand dollars, or two-hundred and fifty thousand dollars will I give up women. They're too much fun."

As early as the war years, doctors had cautioned Ruth to take better care of his health, and he grudgingly followed their advice, limiting his drinking and not going on a proposed trip to support the troops in the South Pacific. In 1946, Ruth began experiencing severe pain over his left eye, and had difficulty swallowing. In November 1946, he entered French Hospital in New York for tests, which revealed that Ruth had an inoperable malignant tumor at the base of his skull and in his neck. It was a lesion known as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, or "lymphoepithelioma." His name and fame gave him access to experimental treatments, and he was one of the first cancer patients to receive both drugs and radiation treatment simultaneously. He was discharged from the hospital in February, having lost 80 pounds (36 kg), and went to Florida to recuperate. He returned to New York and Yankee Stadium after the season started. The new commissioner, Happy Chandler (Judge Landis had died in 1944), proclaimed April 27, 1947, Babe Ruth Day around the major leagues, with the most significant observance to be at Yankee Stadium. A number of teammates and others spoke in honor of Ruth, who briefly addressed the crowd of almost 60,000.

Around this time, developments in chemotherapy offered some hope. The doctors had not told Ruth that he had cancer because of his family's fear that he might do himself harm. They treated him with teropterin, a folic acid derivative; he may have been the first human subject. Ruth showed dramatic improvement during the summer of 1947, so much so that his case was presented by his doctors at a scientific meeting, without using his name. He was able to travel around the country, doing promotional work for the Ford Motor Company on American Legion Baseball. He appeared again at another day in his honor at Yankee Stadium in September, but was not well enough to pitch in an old-timers game as he had hoped.

| Babe Ruth's number 3 was retired by the New York Yankees in 1948. |

The improvement was only a temporary remission, and by late 1947, Ruth was unable to help with the writing of his autobiography, The Babe Ruth Story, which was almost entirely ghostwritten. In and out of the hospital in New York, he left for Florida in February 1948, doing what activities he could. After six weeks he returned to New York to appear at a book-signing party. He also traveled to California to witness the filming of the book.

On June 5, 1948, a "gaunt and hollowed out" Ruth visited Yale University to donate a manuscript of The Babe Ruth Story to its library. On June 13, Ruth visited Yankee Stadium for the final time in his life, appearing at the 25th anniversary celebrations of "The House that Ruth Built". By this time he had lost much weight and had difficulty walking. Introduced along with his surviving teammates from 1923, Ruth used a bat as a cane. Nat Fein's photo of Ruth taken from behind, standing near home plate and facing "Ruthville" (right field) became one of baseball's most famous and widely circulated photographs, and won the Pulitzer Prize.

Ruth made one final trip on behalf of American Legion Baseball, then entered Memorial Hospital, where he would die. He was never told he had cancer, but before his death, had surmised it. He was able to leave the hospital for a few short trips, including a final visit to Baltimore. On July 26, 1948, Ruth left the hospital to attend the premiere of the film The Babe Ruth Story. Shortly thereafter, Ruth returned to the hospital for the final time. He was barely able to speak. Ruth's condition gradually became worse; only a few visitors were allowed to see him, one of whom was National League president and future Commissioner of Baseball Ford Frick. "Ruth was so thin it was unbelievable. He had been such a big man and his arms were just skinny little bones, and his face was so haggard", Frick said years later.

Thousands of New Yorkers, including many children, stood vigil outside the hospital in Ruth's final days. On August 16, 1948, at 8:01 p.m., Ruth died in his sleep at the age of 53. Instead of a wake at a funeral home, his casket was taken to Yankee Stadium, where it remained for two days; 77,000 people filed past to pay him tribute. His funeral Mass took place at St. Patrick's Cathedral; a crowd estimated at 75,000 waited outside. Ruth was buried on a hillside in Section 25 at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York. An epitaph by Cardinal Spellman appears on his headstone. His second wife, Claire Merritt Ruth, would be interred with him 28 years later in 1976.

On April 19, 1949, the Yankees unveiled a granite monument in Ruth's honor in center field of Yankee Stadium. The monument was located in the field of play next to a flagpole and similar tributes to Huggins and Gehrig until the stadium was remodeled from 1974-1975, which resulted in the outfield fences moving inward and enclosing the monuments from the playing field. This area was known thereafter as Monument Park. Yankee Stadium, "the House that Ruth Built", was replaced after the 2008 season with a new Yankee Stadium across the street from the old one; Monument Park was subsequently moved to the new venue behind the center field fence. Ruth's uniform number 3 has been retired by the Yankees, and he is one of five Yankees players or managers to have a granite monument within the stadium.

The Babe Ruth Birthplace Museum is located at 216 Emory Street, a Baltimore row house where Ruth was born, and three blocks west of Oriole Park at Camden Yards, where the AL's Baltimore Orioles play. The property was restored and opened to the public in 1973 by the non-profit Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation, Inc. Ruth's widow, Claire, his two daughters, Dorothy and Julia, and his sister, Mamie, helped select and install exhibits for the museum.

Ruth was the first baseball star to be the subject of overwhelming interest by the public. Baseball had developed star players before, such as Cobb and "Shoeless Joe" Jackson, but both men had uneasy relations with fans, in Cobb's case sometimes marked by violence. Ruth's biographers agree that he benefited from the timing of his ascension to "Home Run King", with an America hit hard by both the war and the 1918 flu pandemic longing for something to help put these traumas behind it. He also resonated in a country which felt, in the aftermath of the war, that it took second place to no one. Montville argues that as a larger-than-life figure capable of unprecedented athletic feats in the nation's largest city, Ruth became an icon of the significant social changes which marked the early 1920s. Glenn Stout notes in his history of the Yankees, "Ruth was New York incarnate—uncouth and raw, flamboyant and flashy, oversized, out of scale, and absolutely unstoppable".

Ruth became such a symbol of the United States during his lifetime that during World War II, Japanese soldiers yelled in English, "To hell with Babe Ruth", to anger American soldiers. (Ruth replied that he hoped that "every Jap that mention my name gets shot"). Creamer recorded that "Babe Ruth transcended sport, moved far beyond the artificial limits of baselines and outfield fences and sports pages". Wagenheim stated, "He appealed to a deeply rooted American yearning for the definitive climax: clean, quick, unarguable." According to Glenn Stout, "Ruth's home runs were exalted, uplifting experience that meant more to fans than any runs they were responsible for. A Babe Ruth home run was an event unto itself, one that meant anything was possible."